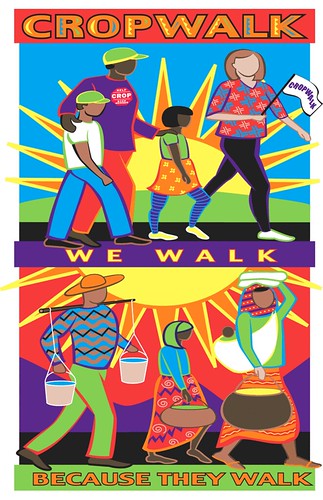

This Sunday afternoon is the CROP walk, a fundraising campaign to end world hunger through Church World Service I've been on many of these walks over the years, especially if you count the ones where I was dragged along in a little red wagon by my parents. It's not even a question for me every year. I'm going. But here's a little something for those of you who may not get the why's and the wherefor's of the thing. It's a true story I recently found in a publication put out by CWS. Although it's a story about water, not food, it still puts a whole new perspective on the mantra, "We Walk Because They Walk."

This Sunday afternoon is the CROP walk, a fundraising campaign to end world hunger through Church World Service I've been on many of these walks over the years, especially if you count the ones where I was dragged along in a little red wagon by my parents. It's not even a question for me every year. I'm going. But here's a little something for those of you who may not get the why's and the wherefor's of the thing. It's a true story I recently found in a publication put out by CWS. Although it's a story about water, not food, it still puts a whole new perspective on the mantra, "We Walk Because They Walk."Water: The Rest of the story...

Our jeep came to an abrupt halt at the end of the dusty road leading to the entrance of the small Malawi village of Maziyaya. We got out, made our way throught he brush and then a cornfield, until we came to a clearing. There stood the new well. The entire "Well Committee" had assembled there to greet us. Ms. Andrea, the president of the group thanked the members of our visiting Church World Service staff group for, as she put it, CWS's kind gift of clean, accessible water.

Because I like to help people here in the United States identify with the long distances that women and children in the developing world have to walk each day to get water, I asked the inevitable question: "How far did you have to walk to get water before the well was installed?"

We had to walk to the river," she answered. "It's about 1 1/4 kilometers from here."

Thinking of the 5 km and 10 km distances that most participants hike in the United States in our annumal CROP Hunger Walks, I said quietly to a colleague standing next to me: "Hmmm.. that's not too bad."

Fate being cruel, my comment — which had not been intended for the women — was heard by the interpreter and, with a lack of any malice, translated to the members of the well committee.

The president of the group, Ms. Andrea, stepped forward and spoke directly to me.

"You're right; it's not that bad &emdash; at least not for grown women. We're used to it. But it's very hard for the little ones."

I felt my face flush. Of course I knew that. I'd worked for 10 years in very poor countries in Latin America. How, ever, had I forgotten how arduous was the daily hauling of water? I began to wish I'd kept my mouth shut.

Ms. Andrea continued: "You see, water's very heavy."

I swallowed hard. I knew that, too; but she was correct in assuming that most Americans, who don't have to haul water every day, may not. There is probably nothing that we consume on a daily basis, besides air, that we take more for granted than the easy availability of clean water. The age-old dictum sounded in my head: "A pint's a pound the world around." I was embarrassed.

"Not to mention the fact," she went on, "that a long of our children are sick."

I'd seen that immediately upon our arrival in the village. It is estimated that 60% of rural families in the developing world still do not have access to safe drinking water. For children who are malnourished, waterborne diseases can bring on diarrheal infections that dehydrate, lowering the body's electorlytes, and can spell death in as few as 48 hours. My discomfort was growing. I was mortified and wanted to go and hide.

"Not to mention the fact that the river is downhill from here and the children had to carry the water back up the hill," she added.

Humiliation is too euphemistic a word to describe what I was feeling. Yet it's important to state that she was saying these things in no way to "put me down" but out of a sincere desire to help me understand just how precious this new well was to them. Still, I was squirming.

"Not to mention the fact," she again went on, "that the river water is polluted with schistosomiasis, guinea worm, and other waterborne bacteria, so that once we'd hauled it back here to the village, we had to do more walking to find firewood in order to boil the water to make it safe to drink."

I wondered: How long would this verbal, even if unintended, flogging go on? I wanted to find a hole and crawl into it when, mercifully, Ms. Andrea put an end to my misery.

"Not to mention the fact," she concluded, "that getting water from the river was dangerous for the children."

"Dangerous? How so?" I asked, sensing a slight opening, the possibility of a slight reprieve, an opportunity to justify myself if, perchance, she might have gone too far out on a limb by using hyperbole with that adjective.

Speaking through the interpreter she explained, again matter-of-factly, "The river is crocodile infested."

It was the coup de grâce.

Today, even after 10 years have passed, when I turn on the water in my kitchen sink it's hard not to think of the village of Maziyaya, and my embarrassing faux pas. Far outweighing my short-lived discomfort of then, however, is the wonderful remembrance today of what a blessing clean drinking water is for one small village, far away, in the heart of Africa.

Joe Moran, Regional Director of Church World Service in the Carolinas, has worked in international development for 36 years.

Be good to each other,

Rev. Josh

050107

1 comment:

Thanks for the link to Neil's site!

I'm in love with it :) Oh, and the poem on Red Leggings is original.

Post a Comment